- Home

- Vikki Warner

Tenemental Page 2

Tenemental Read online

Page 2

I got nervous. I got downright itchy. Would I ever be able to afford not to rent? My coworkers were snapping up ho-hum condos just to get a foothold in this gruesome market, figuring they’d stay a year or three and then cash out, moving up until they had the houses they really wanted. Every property was going quick, now-or-never, for the asking price and then some. This was both terrifying and alluring, and in my upwardly mobile stupor, I felt the unmistakable twinge of wanting in.

I was living with five roommates—all men—and I was burnt out on dirty dishes, moth infestations, food on fire, and pubes in the shower. James and I wanted to shake off the indignities that our living situation forced upon us; we wanted to slow down and have our own space. I felt a primal need to comb flea markets and salvage warehouses for perfect, incredibly cheap antique doorknobs and mirrors. I had an inexact but appealing vision for it: a sweet, old house with art on every surface, a cat or two, a lot of blankets, a decent stereo.

I didn’t have the money to buy anything in Boston, and anyway, I was over it. I’d been there almost five years, and the city had never opened itself up to me. It was expensive and stodgy and nerdy. It felt devoid of opportunity. I had about five friends, whom I loved, but none of them seemed especially happy there either. Being jammed up, in denial of one’s own emotions, is the Boston way. Fun is meted out in small doses. I was in danger of getting carried away on that tide, overextending myself every day just to live in the same boring town.

“I mean, New York could be perfect. If I want to be in publishing, that’s really where I need to be,” I said, on a taking-stock-of-options walk around the neighborhood with James, the dark, old, unaffordable houses of Jamaica Plain looming over us.

“Yeah. For art too. It’s so expensive though; we’d have to live in some shithole. I read an article—there’s like a rat epidemic happening right now.”

In a month or two of further conversations, during which we never discussed the future of our own lives together, only the future of our respective careers and individual prospects, we tossed away the idea of moving to New York. Too expensive, too big, too many people, too frenetic, we reasoned. We were both small-town kids at heart, and an unspoken fear had arisen between us: New York would swallow us whole. New York would quickly poke holes in our fragile psyches, and consequently, in our relationship.

“I’m freaked out about not being right near the ocean. And it takes too long to get to the woods from New York.”

“Well, whatever, we could get on the train and be in Rhode Island in three hours. Or take the commuter train out to the Hudson Valley.”

“True.” Silence.

Another option was to move back to Providence, the adorable but horribly mismanaged capital city of our adorable but horribly mismanaged home state of Rhode Island. We were sheepish about “going backward”; we’d be giving up on big-city life so easily, and we were both embarrassed by this seeming lack of ambition. We wanted to be bold, but we stopped short, failing to double down by moving to the very biggest of cities. We might have been giving up just before some huge payoff, but we knew we didn’t have the drive to go there and fight the hordes of shrewder, cuter, more confident people.

And so, freaked out, we decided to return to Providence. For all the talk of moving to a place that would bolster our careers, our little capital city was likely to kill them unless we both got infinitely more creative in pursuing freelance work. For now, I would keep and commute to my job just outside Boston, an hour each way from Providence on a good day. On the plus side, the cost of living in Providence was half that of Boston, and a third of what we’d expect to pay in New York. To soothe the sting of backtracking, we dreamed up this very jet-setting idea that Providence was just a “base of operations,” from which we would make frequent work-related trips to faraway locales where our editorial or art services, respectively, were desperately needed.

Both James and I had spent a lot of time in Providence as teenagers, going to punk, indie rock, and hardcore shows at Club Baby Head, eating truck-loads of falafel in our Army/Navy surplus fashions, and buying records at Tom’s Tracks. We’d lived there for one year together, before Boston, in a moldering apartment on the East Side where we had to kick out a squad of sleepy art students with yeast infections (there were tubes of Monistat all over the apartment) in order to move in. “No, seriously, we rented this place, and it’s June 1, and you need to leave today.” It’s not clear why we needed to perform the extrication ourselves, without help from our beleaguered landlord; in hindsight, this may have been my first taste of the bewildering landlord archetype.

All told, Providence had been decent to us, and we tried to recognize the pros and cons before committing to go back. It was a fun town, we had friends to hang with, the ocean was close enough to sniff in the air, and there was a thriving art and music community for us to wedge ourselves into—one with infinitely more life in it than the anemic scene in Boston.

The watershed moment came innocently enough. James casually laid it on me.

“I don’t wanna just live in another shitty apartment. I’m sick of renting.” And later, the wheels turning: “You should buy a triple-decker—the rents would cover the mortgage and you’d live there for basically free.”

I sputtered. I don’t remember what I said in reply, such was my shock at his statement, both the concept itself and that his suggestion was made under the category of “you” and not “we.” But he’d struck the match. It had begun.

Just for laughs, and thinking it would surely go nowhere, I called a couple of mortgage brokers. I started trolling Rhode Island real estate listings, my heart pounding, my eyes locked down on rows of search results. In a story that has since become a classic of pre–Great Recession let-the-good-times-roll abandon, I was instantly preapproved to borrow $300,000 after giving up a little personal information, some W-2s, and a couple of paystubs. I had good but very limited credit, being that I was young and had never made a major purchase—I wasn’t even paying back my student loans yet. Still, it was stupidly easy; I ignored the fine print and scrawled my signature, mostly unsure of what I was signing up for.

In an instant, I was on the carnival ride, with the operator asleep at the controls. I couldn’t get off this thing if I wanted to. If I said “I want money,” money would be passed to me from some shadowy entity. Strange as it seemed, everyone was doing it, so why not me? The system obviously worked—nearly every damn homeowner in America had used it, for everything from bungalows to brownstones. Who cared where, specifically, the money was coming from?

Thankfully, I had the foresight (and parental coaching) to decline an adjustable-rate loan, but such loans were repeatedly offered to me, along with several enticing no-money-down, no-income-verification options. The now-infamous “predatory lenders” smelled my fresh blood, but in a rare moment of good sense I spurned them and planned on an old-fashioned thirty-year fixed rate. Thirty years! James and I laughed at the absurdity of signing up for anything on that kind of timeframe, which contributed to our distinct feeling that this wasn’t actually real. We thought it was hilarious that I’d be fifty-seven by the time the house was paid for. We’d picture me at fifty-seven (although probably the woman we were picturing was more like eighty-seven), in a shabby little apartment, the place unchanged in thirty years, the shades drawn, the curtains eaten by moths, the walls crumbling, the 2004-era Ikea furniture having been mended countless times. James never mentioned where he thought he’d end up, but clearly he was not to be counted in this scenario. So why was I about to buy a house for us to live in, when he could cut out at any time, and when he wasn’t interested in talking about us in the future tense? And when I wasn’t sure what I wanted, either?

Despite these moments of panic about the future, I spent hours online, parsing and reparsing more listings, funneling my nervous energy into a deepening real estate obsession. I was in it now, riding hard the impossible fantasy of finding the perfect house in the perfect neighborhood at the pe

rfect price. I was hurtling toward something unknown, and even though nothing was yet decided upon, and no real obligations yet created, it felt inevitable. The recurring theme was that if I did not buy a house right now, I would never be able to afford one. Because prices were just going to keep climbing—FOREVER.*

Ever the haven for the misunderstood and the contrary, Providence has been attracting oddballs since 1636, when it was established by one Roger Williams, a Puritan minister who left England, and was subsequently banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, for espousing freedom of religion. Avoiding deportation to prison in England, forced out of a Massachusetts that had become very hot for a person of his beliefs, Williams moseyed south of its confines, and was offered refuge with the Wampanoag and Narragansett people; the latter eventually sold him the land that became the city, which he named in honor of “God’s merciful Providence,” deeming it “a shelter for persons distressed for conscience.”

By most accounts, Williams is portrayed as a fair and respectful man; he opposed slavery, devised the concept of separation of church and state, and enjoyed a long relationship of mutual trust with the Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes. As colonial figureheads go, Rhode Island’s are pretty good. The State House is topped by the Independent Man, a golden statue of a loincloth-garbed, spear-carrying man with an anchor at his feet; he represents our strength as well as our renegade streak, and Rhode Islanders are very into him as an icon.

Providence was an early manufacturing leader in America. The first textile mill in the United States was built just a few miles away in Pawtucket in 1793. Mill complexes quickly popped up all over the state and city; employing generations of factory workers, they cranked out textiles, tools, silverware, and jewelry. Rhode Island calls itself the “birthplace of the industrial revolution,” and although that is a messy credit to claim—considering the awful things our country did, and does today, in the name of “industry”—the state claims it proudly.

So this state may have once been on its way to national respectability. But give any set of beliefs or commonalities a few hundred years to stew in the pot of a semi-insular population, and they get twisted. The offspring of the colonial settlers, plus that of later immigrants mainly of English, Portuguese, Italian, French Canadian, and Irish descent, have internalized our founders’ rogue spirit and added generations of spin on it, not to mention an ear-curdling accent. It’s averaged out to a few basic traits many of us have in common: crankiness, sarcasm, tough talk, the ability to take (and tell) a joke, and lazy yet hostile driving tendencies. It’s a hard-charging, pint-sized buoyancy that can’t help but be endearing and often infuriating.

There’s also a heavy distrust of government at all levels, because if there’s one thing we’ve got, it’s corrupt officials. Generations of them, each one building on the air of permissiveness and selfishness that came before. Each official painted in his own beautifully nuanced shade of braggadocio, finding new and creative ways to cheat at “serving” the public. “Distressed for conscience,” indeed. Innumerable deals were struck between city government and organized crime when the latter ran the show from the mid-1950s through the 1980s. The patron saint of Providence con men is the late former Providence mayor/twice-convicted felon/fame seeker/all-around blowhard Vincent “Buddy” Cianci, whose very name continues to incite devotion and rage in equal proportions among Providence residents.

My Providence brethren have simply learned to live with the patterns of waste and grift in the city, mostly by devising artful new ways to complain and joke about it in our hardass Yankee way. But we stay here because we really love this place. We even love that it is often openly terrible. New Englanders love punishment.

Providence is a college town, and we’ve ticked a box in each category: a vaunted Ivy (Brown University); the best art school, some say, on the continent (Rhode Island School of Design [RISD], a.k.a. RIZ-dee); a culinary/hospitality training ground (Johnson & Wales University, or “JAY-Woo”); a traditional Catholic college with a creepy, blank-faced Friar mascot (Providence College) and a public school serving primarily local students (Rhode Island College). Neighborhoods cater to the differing tastes of each student body with run-down Irish pubs with buzzing Bud Light neon signs for the Catholic school and fancy coffee shops and cafes for Brown and RISD. Most locals have some sort of bone to pick with the universities—they take over the choicest bits of real estate in the city, and—due to their mostly tax-exempt status—occupy them, flowing money back to the city only at their own whim. Students crowd the apartment rental market; they are loud, they are messy, whatever. But without the influx of students that comes every year, and without the people who choose to stay after college, this would be a far less lively city, and a far more broke one.

There is a bit of local lore that says if you drink from a particular fountain in the city, you might leave Providence, but you’ll be bound always to return. The only part of this statement that is surprising to me is “you might leave Providence,” because most of us native Rhode Islanders are shackled to this place on a permanent basis. Our state’s flag carries the very fitting image of an anchor; the same image adorns a popular bumper sticker that reads “I Never Leave Rhode Island.”

On a short walk in Providence, you can be alternately buoyed by the beauty of the place and its people, and horrified by the mountains of litter, the boarded-up houses, the threatening tenor of peoples’ interactions, the alarming amount of street drugs, and the number of straight-up assholes looking to fight or harass women. A new wave of city leadership has taken over, and things have begun to improve, or at least lurch toward modernity. Following a lengthy line of white guys, two consecutive Latino mayors have started us up the long hill of tightening the city budget, sniffing out corruption, figuring out what to do with abandoned properties, reducing crime, and improving public education and housing. But there’s still an Old Guard in this town, and their unblinking refusal to accept change—even when that change is geared toward creating stronger neighborhoods, healthy small businesses, better-educated kids, and new jobs—is bizarre and chilling.

When I made the succession of moves that would bring James and me back to Providence, I did it without an adequate understanding of what I was signing up for, the struggles present in the place where we were planning to make a life, and whether I was up to the task. All of those considerations were happenstance to me back then. I never deeply considered what sort of neighborhood I wanted to be part of. I never pinpointed exactly what I wanted my house to look like or contain. I never nailed down my goals for homeownership or a basic timeline for how long I planned to live in said house. I never read a book about real estate, took a class, or even googled “advice for landlords.” I thought all it would take was a modest pile of dollars and a little common sense: the tenants pay the mortgage, I do a bit of upkeep, make nice with everybody, fill the place with secondhand but still-classy furniture, and get to use my own paycheck to buy champagne and tropical vacations. Right?†

On a one-day romp around some of the most unloved properties of the west side of Providence, I looked at the interiors of exactly three triple-deckers before I saw the house I eventually came to buy. Some of the apartments were laid out in the infamous railroad style, where one walks through the living room to get to the kitchen to get to a bedroom, or some variation thereof. They were old houses, but they had been pathetically renovated over the years to feature acres of particleboard and thin, bedraggled carpeting. Bare wires and naked light bulbs hung down. Sunlight strained to illuminate dusty, junk-filled rooms with blankets over rickety windows. Huge, ancient boilers brooded in decaying basements. These houses were beaten down, stained, tired. Perhaps some bit of panic set in then—I saw what I could afford, and it did not inspire excitement or even mild interest. My normally clear head felt muddled; counter to any reasonable instinct, somehow it felt like the only way to put my brainwaves right was to just go on and buy the first decent house I saw.

That means I

made a monolithic life decision—one that would factor heavily into my existence for potentially the next thirty years—in the space of a couple of hours, and after seeing practically nothing else to which it could be compared.

Since starting the loan process, I had been subject to financial reality check after reality check, and it was now clear: I had very limited resources. Those bank statements I’d been so proud of now looked comically paltry. I moved on to accepting that no matter how many listings I pored over and how many beautiful, way-out-of-reach houses I ogled, I would end up settling for a house that didn’t knock me sideways. This was to be a practical endeavor, I told myself, not an emotional one.

“Besides, you can sell it in a few years if you want to,” James noted. As if that would be easy.

* Not what happened.

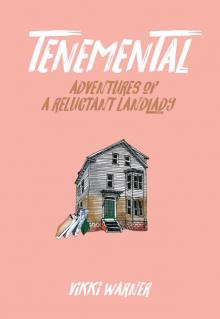

Tenemental

Tenemental