- Home

- Vikki Warner

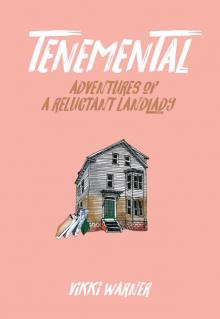

Tenemental Page 9

Tenemental Read online

Page 9

Once dead at last, the relationship detangling begins in earnest. Who will move out? Will anyone stay? Who gets to keep all the best records? Who gets to keep the couch? What happens to the cat? It’s inhumane to have to consider such things when in the midst of an emotional catastrophe. The home base becomes the seat of relationship mourning, the place where all objects, seasons, and fleeting feelings remind the mourner of what she had, and how she has fucked it up. It’s hard to be there; it’s hard to leave.

Amid dreadful, protracted screamfests with Elvin, Caroline had been living upstairs for a month or so when Cal—also cracking under interrelated stresses—moved out and returned to Baltimore practically unannounced. Determined, Caroline found yet another roommate—a real feat considering her precarious emotional state. We all hoped Elvin would tire of this arrangement and move out, but he was entrenched by then, harnessing a spiteful fortitude to outlast her. After a few contentious months, she conceded. The opportunistic nature of the situation was the kicker—either of them could flip at any moment, and the object of their frustration was always close enough to casually eviscerate. This could not go on indeterminately. Embattled, Caroline and her roommate again packed up their things and moved to another house in another part of town, one where drama wasn’t assumed, and the walls weren’t painted in sad.

Really, though, is there something in the walls here? In the pipes? Some jilted spirit that demands a reckoning? Perhaps a bad energy that I need to cleanse? Friends have suggested burning sage and performing healing chants.

The grand, operatic drama of synchronized relationship meltdowns and apartment scrambling was over, but it had exacted a toll on all of us. The tension subsided, and within a few weeks it no longer felt as if the roof was going to blow off volcano-style. There was relief in knowing that these great ladies could now move on sans male encumbrances, but I missed perching on the stoop talking about life stuff with Cal or posting up in the garage on a rainy night with Caroline, smoking and polishing off a cheap jug of wine. From this point forward, with few exceptions, my tenants would all be men.

Having women in the house made the place feel more looked after, and it was dreamy to be mere seconds from an impromptu hang at all times. Being in each other’s space gave our relationships an immediacy, a real-time understanding of one another. We looked at each other and recognized the fight; we wordlessly agreed to support one another. Even toward the end of their stay, when these women were feeling out of control, when the high drama was at its climax, they kept it together. We treated each other with sweetness and caring. They respected me and the house, and—not to be taken for granted—made it smell really nice. They told me how much they loved living here and didn’t want to leave. But circumstances made them leave anyway.

When I later ran into any of the inhabitants from the PennHenge Couples Meltdown period, they usually avoided looking at me directly. They were uneasy. Perhaps I was a representative of a bad place, a portal to bad times, and to look at me meant acknowledging that the place still existed, somewhat unchanged, with me sitting tattered at the unhealthy helm. That old shiver floods back with one look at my face.

Caroline later admitted that she was pissed at me for a while after she left because I didn’t stand up for her strongly enough when things with Elvin were boiling over. She was right. I took the path of least resistance, reluctant to step into the conflict; instead of telling Elvin to go, I let them work it out for themselves—which did not produce an amicable solution, but rather scarred Caroline in ways that I now know took her years to heal. I wish I could take that back; I wish I could have nurtured Caroline at that time, instead of deflecting involvement. Frankly, I was intimidated by Elvin’s anger—gleaming, sharp, and omnipresent as it was back then—I thought he’d hurt me too.

This period of breakups and apartment shuffling may have been the moment when my idealistic desire to install a harmonious group of lovers and thinkers under my roof began to slip from view, engulfed as it was by the pressures of staving off said lovers’ and thinkers’ emotional disasters. I began to think maybe just paying the mortgage and keeping the rooms occupied was enough of a challenge.

I was drained from seeking good people out, inviting them in, and then watching them leave. My level of caring notched slightly down; I was tired of letting the house dominate my thoughts, and in my fatigue I thought leaving it all up to chance might work as well as controlling every detail. We were sliding backward into what I justified was a more businesslike arrangement: from “friends who live in the same house” to straight-up tenants and landlady. You pay me, you live here. Simple and sucky. PennHenge was once comprised of people with lots in common, who happened to live together; now I was flipping that dynamic on its head, setting up a zone where people lived together, and had little in common.

But this was a risky move, for my own psyche had by now become intertwined with PennHenge such that when the house or its occupants were unwell, so was I. Being nice and making sure the heat stayed on seemed somehow too basic. I still hankered for the close bonds that had been so slippery throughout this experience. Do other landlords feel this way, I wondered? Do they fret over their houses as if they’re troubled children, loved but in danger?

I suppose the house is my dependent. In a way—and arbitrary as such things are—it’s the only badge identifying me as an adult.

Elvin brought in his friend Johnny, a metalhead body piercer, as his new, post-breakup roommate. Johnny had a young daughter who would stay with us for a day or two at a time. Being heavily pierced, pale, hangdog, and clothed entirely in black, Johnny looked hardened and unfriendly. He seemed tested to the limit by his own existence, his persona a bald statement of negativism. He didn’t say a whole lot, and he wasn’t exactly a barrel of laughs, but when we did talk, I always felt that he ran deep, and that he cared. He’d admire the garden and we’d talk about his family, his daughter, his job, and mine too. I worked hard to get a laugh out of him; each time he huffed out a quick, staccato cackle, I felt a glimmer arise from him.

Between Johnny and Elvin, the first floor was morphing into a nihilist bachelor pad. Caroline’s cheeky decorative touches were slowly wiped from the apartment; the general feel of the place became darker and dirtier as the windows were covered with thick cloth, such was the boys’ aversion to natural light. A thick wall of sludgy guitar blasted forth from the stereo. They never cooked; they didn’t clean. I imagined Johnny’s daughter sitting among a pile of beer bottles and pizza boxes, waiting for their weekly outdoor time: “Dad, can we go now?”

Upstairs from Elvin and Johnny, the second floor was newly empty. I did some small-time work on the place—painting and macrolevel cleaning and putting new knobs on drawers. But there was no rent coming in, and being responsible for this extra share of the mortgage meant I was bur-roke. I made the friend rounds, trying to be relaxed about scaring up new tenants, but interest was low and leases unable to be broken. The spectacle of recent relationship failures in every corner of the house had roundly defeated me, and I was not entirely competent to seek emotionally healthy, new second-floor tenants. I was frustrated, a touch desperate, and maybe a little bit in the mood to fuck things up. From this crumbling ledge, I stepped off into a blinding wind of unsound tenants.

But it was also glorious summer in Rhode Island, and I was a few weeks into dating someone new. I’d seen Seth at an art opening and made a shameless beeline for him. This behavior was way out of my norm, but I saw him sitting by himself, sipping a drink in a butter-yellow sweater, and my feet sort of moved themselves. I saw him again a few weeks later, at a show, and the same thing happened.

Seth was a very talented audio engineer, a thoughtful, funny guy, a loyal friend, and someone who could effortlessly make any location or situation fun. He worked for an old friend of mine, so I slid right back in with his familiar crowd. Seth and I lolled around on the beach, went to the movies, sang giddily along to every song on the radio, laughed constantly. It was a conn

ection forged in fun, so different from the one I’d shared with James, which had been forged in intensity and suffering in the months after his dad passed away.

I wanted to be around Seth as much as possible, and he clearly felt the same way, but we played it cool because I was only a few months out of that nearly nine-year thing with James. At thirty to his twenty-one, I was also nine years older than Seth—somebody prepare the numerology charts—which one minute seemed crucially ominous and the next like a nonissue. Seth was short, skinny, and scruffy and wore holey jeans and threadbare T-shirts; being roughly the same size, we traded clothes.

Seth’s life revolved around music, both because his curiosity for it was so intense, and also because his job was strangely 24/7. Although a lot of the music he recorded was intentionally difficult, sloppy, or impenetrable, his own understanding of music was clean and precise. He rarely got a day off; he enjoyed being needed at work, being “the only one” who could fix a problem or be on call for one thing or another.

But he was graced with a day off on the Fourth of July, and we traded texts with barely concealed excitement. I was delirious, eager to spend the day with him, but I wasn’t sure whether our relationship standing yet included hanging out on holidays. He texted to suggest a bike ride from Providence to the seaside town he grew up in, where we’d hang out with his family, watch a parade, have a cook-out, drink American amounts of alcohol. Shocked by this seeming early admission of heavy interest on his part, I was all in. Any mainstream women’s magazine in existence would confer grave importance to my having been asked to meet the family, but our relationship was only three weeks and a handful of dates old. In this act, he was bringing me closer, yes, but not because he gave credence to any of the traditional milestones of dating. He was neither a player of games nor an assigner of meaning, not that I quite knew that yet. I did know that if there was one thing I was down to do, it was to jump into something messy and poorly defined and full of cloaked passion. I’d been love-starved for years.

Getting on our bikes a bit late, in danger of missing the parade, caffeinated but with no food in our bellies, improperly attired, and not in possession of even a bottle of water, Seth suggested that we make up for lost time by biking faster than usual. I spent the hour-and-a-half ride out of breath, my legs on fire, trying to catch his jean-clad ass as it continually disappeared on the bike path ahead of me. This would become a metaphor for our relationship: he moved so fast; he couldn’t be still; he sometimes willingly vanished from my horizon.

When we arrived at his parents’ house, I was red and hyperventilating, sweating beyond the heat, unable to push the pedals even one more time around. My guts flailed. But I loved his parents instantly; warm, funny, reliable, doting, and still clearly in love, they welcomed me. His mom cracked witticisms about her casual garb for the day (“this is my Independence Day, Vikki!”); his studious yet rugged dad threw the Frisbee for the dog. I felt instantly included in the family, let in on all the jokes, part of a united front fortified by potato salad and hummus. Getting a ride with Seth’s dad back to the city, resting in the backseat of their Subaru wagon, having spent a sun-soaked day eating, kayaking, swimming, and walking the dog around their suburban neighborhood in its silly, patriotic revelry, I was giddy. These beautiful people had raised this sweet man. It felt like every force—internal and external—was propelling me toward him.

As I floated deeper into the reverie, I had to come up for air at least long enough to half-assedly rent out the second-floor apartment, which had now been empty for a couple of months. Through a friend of a friend, a solution came in the form of a turtle-faced guy with the intriguing nickname of Dougie Peppers, who worked at an upscale grocery and seemed, if not charming, at least stable enough. But stories started percolating my way—immediately after he moved in—alluding that he owed more money and had stolen more stuff from my friends around town than could possibly be coincidental. Yeah, he seemed kind of squirrely, for sure, but I wasn’t going to fall for the small-town scuttlebutt without giving him a chance.

He started out with one roommate, a rangy, spacey, tweaked redhead punker named Cheryl, but within weeks he was moving other friends in (without asking or even informing me) so he could get help in paying the rent. As one new recruit would prove unable to cough up cash—or unable to handle the personalities involved—another would take his place. There were three new arrivals in rapid succession. The third one was a charmer I dubbed Stoner Joe—part hippie, part raver, part sleazeball, part acid casualty, part rap-rock Jesse Pinkman, he was an intoxicating mix. The instant I laid eyes on Joe, I felt a strong urge to change the locks on the doors. He always looked to be on the verge of a meltdown or a bender. He had a talent for saying the creepiest thing at the moment you turned away, when you thought you were done talking with him. I would sneak out to work in the garden, hoping to evade him, but he would come outside shirtless and stretch out in a lawn chair with a bong, sighing into the sunlight, vaguely hitting on me, and chugging beer. He brought home an abandoned pit bull, which humanized him a bit but added stress to the house as the untrained dog barreled through, barking and jumping on people, Joe making no move to calm him down.

This crew was loud, drunk, petty, and fiery. They fought like siblings, in a whiny fashion, constantly. They seemed unable to stay out of one another’s hair, unable to understand the concept of a peaceful existence. The tension was way up and the drugs were being doled out at frequent intervals.

Stoner Joe, Dougie Peppers, and Cheryl were often unable to pay the $700 rent in full. Sometimes, they’d pay half of it; sometimes, they’d pay two-thirds. It was difficult to impress upon them that the monthly rent amount was not merely a suggested retail price but rather a contract with which they were bound to comply. I uneasily bugged them for money every month, stressing one moment about asking them and the next about not being able to pay the bills. I didn’t like these people as human beings—and as tenants, they were beyond the pale. It was soul-crushing to endure even a one-minute conversation with them.

Seth wanted little to do with PennHenge. This wasn’t a particularly illustrious time in its tenure, so I couldn’t take much issue there. Even I wasn’t jumping at the chance to be affiliated with it. I remember his reaction upon walking into my apartment for the first time: unimpressed. “Charming but off-kilter” didn’t do it for him; he preferred precise and sleek, the same way he did his job. Of the newly renovated bathroom, he backhanded, “It’s the nicest room in the house.”

Although he was now very clearly my full-fledged boyfriend, there was no doubt that I was still going it alone. I hesitated to ask him to invest his brainpower or ultra-limited free time to help me with some house chore. I thought he might see such a request as a drag on our fun. I daydreamed that in a year or two he might want to move in with me, but even as I considered it, I felt him hoping I would never ask. His lack of interest hurt a little because my house was an extension of me—including (and especially) the unkempt parts. But I didn’t buy the house with Seth, I told myself, so he was under no obligation to spend his rare nights off helping me nail trim into the window frames. He did his best to contribute, but even an unusually stable twenty-two-year-old man has limited tolerance for old-house problems.

I reasoned: If he loves me but doesn’t love my house, we can find a work-around. I tabled the thought, knowing it was too early in the game to be strategizing in that direction.

Gathering up whatever toughness resided in me, I eventually had to boot out the Dougie Peppers/Cheryl/Stoner Joe trifecta. I was horrified to have to be the enforcer, but the situation was past the point of reason. These guys were a festering mess, and every day they stuck around, the stain sunk deeper in. I had to preserve my self-respect. If I didn’t do it soon, they’d only get more entrenched, which meant they’d break more beer bottles, yell more, not pay the rent more, act like petulant assholes more.

After several minutes of deep-breathing exercises, I knocked on their door, my

breath shallow. Cheryl opened it. I clenched my fists by my sides and opened my mouth to speak. As I did, she preempted with, “We’re movin’ out. We’ll be out in a week. Is that what you were coming to ask?” I stuttered back at her that yes, that was it, and actually thanked her—because god, it was such a relief to have it over with, no screaming, no fighting, no threats. I kicked into gear, said something like, “Yeah, thank you, please leave now; I’d really appreciate it.” I almost felt badly that it had gone so smoothly. And they did go away as scheduled, leaving me to that same old dilemma: empty apartment, insufficient income, and lack of exceptional examples of humanity clamoring to be part of my life experiment.

When the second floor was again empty, I did a new round of cleaning and painting. Windows open, spirits chased out, hot water, soap, mops, the whole bit. These people didn’t have much stuff that couldn’t be jammed into milk crates, so they didn’t really leave anything behind—just a few scratched records and a lone, crusty crack pipe hanging out on a shelf in the closet.

Loneliness is sometimes recognizable only in retrospect. In the day-to-day, there is stuff to do, so much busyness masquerading as fulfillment, such that you may not notice the cracking of your mental terrain. Someone I love once told me that I like adversity—which seems like a really self-important thing to repeat to you now, but in the context of this person’s comment, it was meant in a literal sense that I do not like the way to be too easy. If I have the choice to walk somewhere or to drive a car, I will always walk. If it starts pouring while I’m on my bike, I take it as a fun novelty. If I get lost in the woods at sundown, a little thrill runs through me. So, maybe I enjoyed the adversity of living with difficult people and of seeking devotion from a man who, when pressed, told me he cared about me, but never that he loved me. Someone with whom I could get a month deep and stay there for years, trying to coax more out of it, bumping up against the end of it again and again.

Tenemental

Tenemental